It is with enormous pleasure that I welcome Pete Langman onto the website today. Pete is an academic, editor, rock and roll guitarist and author of three books. His writing has also appeared in a plethora of publications ranging from The Guardian to Guitar and Bass Magazine.

Alex: Tell me a bit about yourself, Pete.

Pete: Goodness, start at the beginning, why don’t you? I was born in the home counties but we moved to Australia when I was four. And promptly moved back again. I always got the feeling it was a dry run before emigration that didn’t work out but my mother denies it ... anyway, I have a strange and disconnected set of early years memories as a result, mixed in with a lot of family lore which I would dearly love to remember but simply cannot see. The time in Bali where we spent a week or two in a hut by the sea (there was one hotel on the island), and every morning my parents would hand me to a man who I suppose must have been the caretaker of the huts and he would stick me on the back of his bike and cycle here, there and everywhere. I mean, what an awesome memory to have of your childhood, right? I guess it would be, if only I had it ... the upshot was that by 1972 I had lived on a beach in Bali (amongst other places), been to two Australian schools and travelled half way across the world. A couple of years later I found myself in a convent school in Norfolk standing accused of being part of a Papist conspiracy by a nun.

I grew up in a continuously renovated farmhouse in the middle of Norfolk in a village where the house opposite us was still visited by the nightsoil wagon. Flushing toilets were a rare luxury (we had them, mind). I spent a lot of my time sat in trees watching birds and animals. I much preferred that to being at school where I was a solid if unremarkable student with few friends. I was mostly an anonymous child.

As for writing, it was never something I did. I wasn’t the child who wrote great epic fantasies at age 9 and wanted nothing but to be a writer. If anything I wanted to be a vet (but was too squeamish and probably not clever enough) or an environmentalist. I would get into arguments about CFCs and the ozone layer with adults when I was barely ten. I started reading early (or so I’m told), but when interviewed for the school I attended from the age of 8 or 9, the headmaster was very worried that I couldn’t read at all. He based this on my answer to his question, ‘what do you think of Biggles?’ Who’s Biggles? I replied. I read history books and encyclopedias and when I dared to sneaked a peek at my father’s books, egyptology and so on. I was reading Solzenitsyn at 12 but never really had the urge to write.

I was 15 when I discovered the electric guitar. By 17 I’d won a place in and been expelled from military academy, caused an awful lot of trouble at another school, and left home. I accidentally achieved ‘A’ Levels in English and Psychology while painting houses, working in a pub and playing in a couple of bands. Then I went to Los Angeles to study music.

I know, ‘tell me a bit about yourself’ ... not my whole life story.

There is a point to this.

By 1995 I was teaching guitar at London’s Musician’s Institute and was pretty well known as an excellent player who couldn’t get a gig. I was asked to write a monthly column for The Guitar Magazine and before long realised I enjoyed the prose more than the music. By this time I was the one in the band who would be reading Dickens on the plane or on the bus while the rest of the guys were being all ‘rock and roll’. Something had to give. It was music. I ‘retired’, started writing and went to study English at Queen Mary UoL in Mile End. Things got out of hand and I ended up with a PhD. I’ve done little but mess around with words ever since.

Alex: Tell me a bit about yourself, Pete.

Pete: Goodness, start at the beginning, why don’t you? I was born in the home counties but we moved to Australia when I was four. And promptly moved back again. I always got the feeling it was a dry run before emigration that didn’t work out but my mother denies it ... anyway, I have a strange and disconnected set of early years memories as a result, mixed in with a lot of family lore which I would dearly love to remember but simply cannot see. The time in Bali where we spent a week or two in a hut by the sea (there was one hotel on the island), and every morning my parents would hand me to a man who I suppose must have been the caretaker of the huts and he would stick me on the back of his bike and cycle here, there and everywhere. I mean, what an awesome memory to have of your childhood, right? I guess it would be, if only I had it ... the upshot was that by 1972 I had lived on a beach in Bali (amongst other places), been to two Australian schools and travelled half way across the world. A couple of years later I found myself in a convent school in Norfolk standing accused of being part of a Papist conspiracy by a nun.

I grew up in a continuously renovated farmhouse in the middle of Norfolk in a village where the house opposite us was still visited by the nightsoil wagon. Flushing toilets were a rare luxury (we had them, mind). I spent a lot of my time sat in trees watching birds and animals. I much preferred that to being at school where I was a solid if unremarkable student with few friends. I was mostly an anonymous child.

As for writing, it was never something I did. I wasn’t the child who wrote great epic fantasies at age 9 and wanted nothing but to be a writer. If anything I wanted to be a vet (but was too squeamish and probably not clever enough) or an environmentalist. I would get into arguments about CFCs and the ozone layer with adults when I was barely ten. I started reading early (or so I’m told), but when interviewed for the school I attended from the age of 8 or 9, the headmaster was very worried that I couldn’t read at all. He based this on my answer to his question, ‘what do you think of Biggles?’ Who’s Biggles? I replied. I read history books and encyclopedias and when I dared to sneaked a peek at my father’s books, egyptology and so on. I was reading Solzenitsyn at 12 but never really had the urge to write.

I was 15 when I discovered the electric guitar. By 17 I’d won a place in and been expelled from military academy, caused an awful lot of trouble at another school, and left home. I accidentally achieved ‘A’ Levels in English and Psychology while painting houses, working in a pub and playing in a couple of bands. Then I went to Los Angeles to study music.

I know, ‘tell me a bit about yourself’ ... not my whole life story.

There is a point to this.

By 1995 I was teaching guitar at London’s Musician’s Institute and was pretty well known as an excellent player who couldn’t get a gig. I was asked to write a monthly column for The Guitar Magazine and before long realised I enjoyed the prose more than the music. By this time I was the one in the band who would be reading Dickens on the plane or on the bus while the rest of the guys were being all ‘rock and roll’. Something had to give. It was music. I ‘retired’, started writing and went to study English at Queen Mary UoL in Mile End. Things got out of hand and I ended up with a PhD. I’ve done little but mess around with words ever since.

Alex: How would you describe your writing, and are there particular themes that you like to explore?

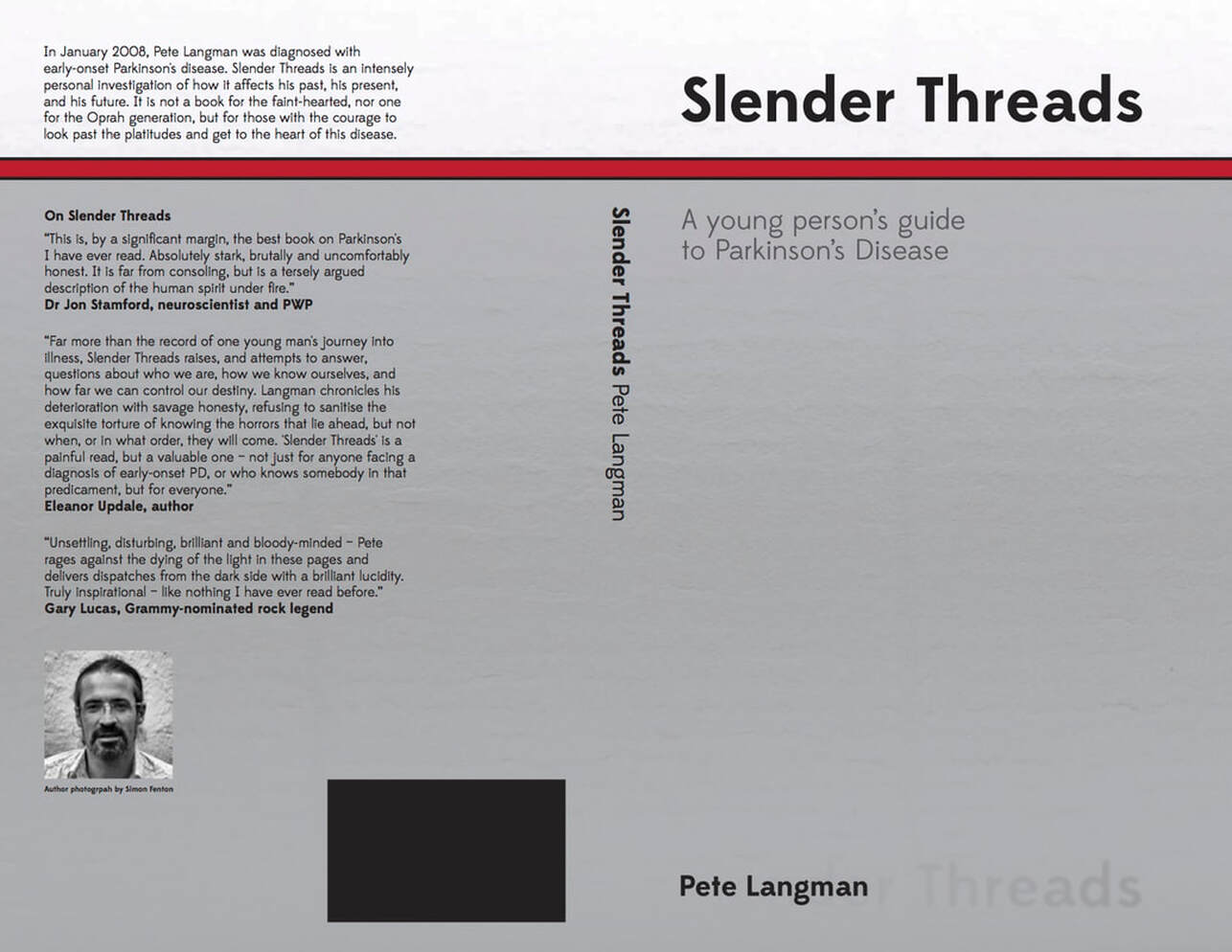

Pete: I’m not sure I can describe my writing, as I run the gamut from academia (my latest is a forthcoming collaborative piece on archival theory) all the way down (or up) to children’s books (I wrote a sadly unpublished book about how Father Christmas used to be a pirate). In between there’s a play about the ‘Shakespeare authorship question’, a cricket-based murder/mystery/farce radio script, a book about living with Parkinson’s disease, one about cricket, several unpublished novels and all manner of other stuff besides. If there’s a theme that links them all it’s identity. Because that’s really the only question, right? Who am I? Who are you? Who are we? It covers everything.

Actually, I suppose I can describe my writing. It’s not as clever as it thinks it is. Except when it’s cleverer. Problem is, I can’t tell the difference.

Alex: Are you a writer that plans a detailed synopsis or do you set out with a vague idea and let the story unfold as you write?

Pete: I think this is one of the greatest myths about writing. A draft that unfolds as you write is merely a detailed synopsis with all the umms and ahs left in. I do both. I know exactly what’s going to happen as I write. I know the plot, I know the ‘incidents’, and all that stuff. And I change the plan as I go along. Or as I have a new idea for a character, or as a character develops in an unexpected way. As a reader, I think it’s obvious and a little dull when you can sense that the author knows exactly what is going to happen as they write. What’s more, it means you can generally tell, too. Writers love to put little clues in, foreshadowings and all that. Readers notice. Which is good, because that’s what they’re for – but it’s also bad, as it sets up expectation. In the same vein, it’s bloody irritating when you can feel an author searching around for something that they can’t quite grasp. It’s often obvious when a writer doesn’t quite know what’s happening. These are subtle things, obviously, but they’re both true. The trick is to keep the reader on their toes just enough ... too much and it’s unfocused, too little and it’s over-controlled. I’m not sure it’s a trick I’ve mastered.

So the answer to the “plot or pants” question is to plot with your pants on, and ride your plot by the seat of your pants. That’s what I try to do. Have enough structure to keep it coherent, and enough flexibility to keep it exciting. How much I succeed is another matter, of course. With apologies to Mike Tyson, everyone’s got a plan until their book punches them in the face.

Alex: Tell us about your latest novel.

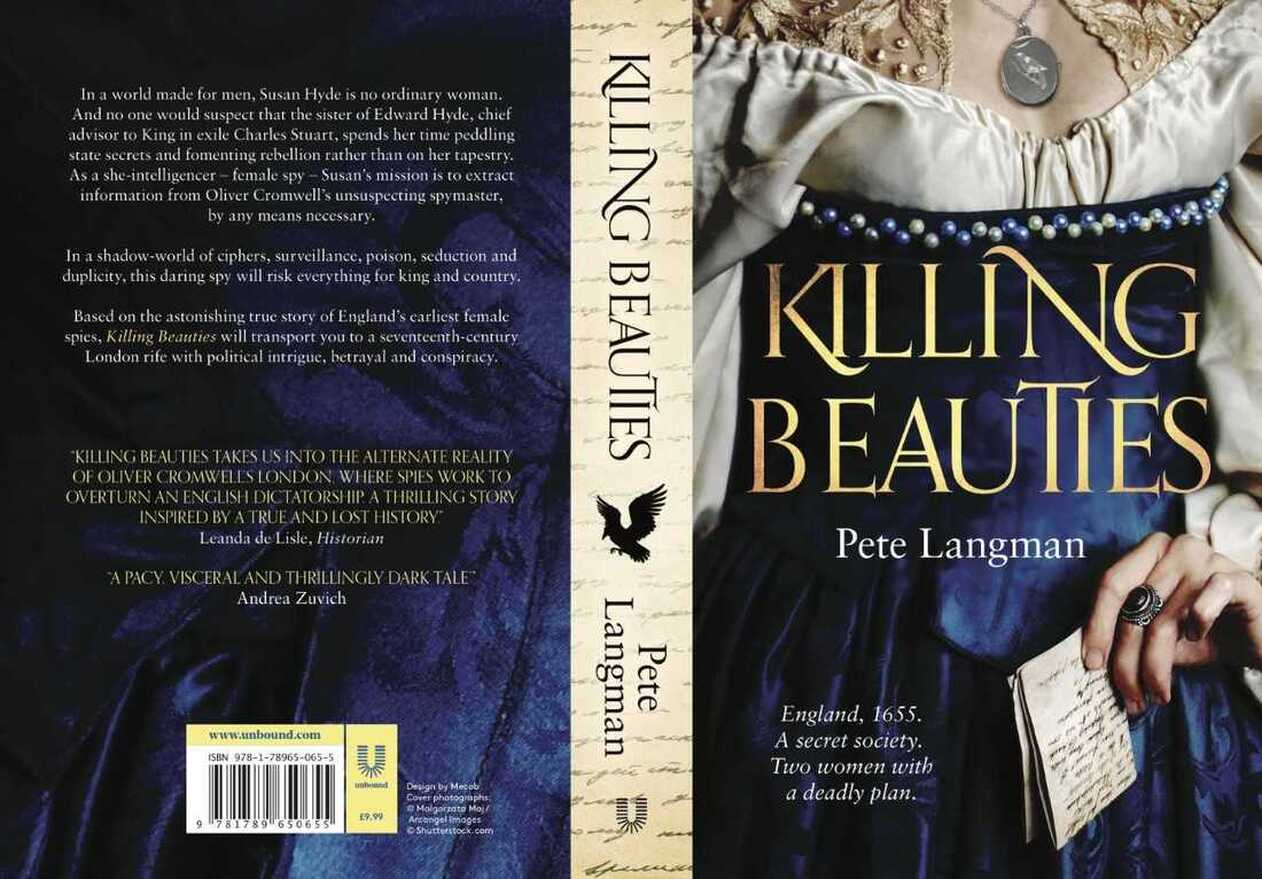

Pete: My latest novel is called Killing Beauties: the chronicle of Susan Hyde, and it’s a work of historical fiction. Or fictionalised history. I’m not sure which. It follows a year in the life of Susan Hyde during the Interregnum of the 1650s, the period after the civil war(s) when Cromwell ruled the country. Susan, the sister of the king-in-exile Charles Stuart’s chief advisor Sir Edward Hyde, is sent on a mission to discover how John Thurloe, Cromwell’s Secretary of State and de facto spymaster, is uncovering all of the plots hatched by the royalist ‘secret’ society The Sealed Knot. Her job is to infiltrate his network, and then kill him. In this plot she is assisted by a firebrand called Diana Jennings and an all-female secret society called ‘les Filles d’Ophelie’, or the daughters of Ophelia. Things get out of hand ... and if I went any further, I’d be telling you the plot.

The book has two twists. The first is the plot twist, which I’m obviously keeping to myself, and the second is the fact that both Susan and Diana were real women who actually worked as spies for the royalist cause. Well, to be fair, Diana only ever truly worked for Diana Jennings, but that’s what made her such fun to write (and, hopefully, to read).

Pete: I’m not sure I can describe my writing, as I run the gamut from academia (my latest is a forthcoming collaborative piece on archival theory) all the way down (or up) to children’s books (I wrote a sadly unpublished book about how Father Christmas used to be a pirate). In between there’s a play about the ‘Shakespeare authorship question’, a cricket-based murder/mystery/farce radio script, a book about living with Parkinson’s disease, one about cricket, several unpublished novels and all manner of other stuff besides. If there’s a theme that links them all it’s identity. Because that’s really the only question, right? Who am I? Who are you? Who are we? It covers everything.

Actually, I suppose I can describe my writing. It’s not as clever as it thinks it is. Except when it’s cleverer. Problem is, I can’t tell the difference.

Alex: Are you a writer that plans a detailed synopsis or do you set out with a vague idea and let the story unfold as you write?

Pete: I think this is one of the greatest myths about writing. A draft that unfolds as you write is merely a detailed synopsis with all the umms and ahs left in. I do both. I know exactly what’s going to happen as I write. I know the plot, I know the ‘incidents’, and all that stuff. And I change the plan as I go along. Or as I have a new idea for a character, or as a character develops in an unexpected way. As a reader, I think it’s obvious and a little dull when you can sense that the author knows exactly what is going to happen as they write. What’s more, it means you can generally tell, too. Writers love to put little clues in, foreshadowings and all that. Readers notice. Which is good, because that’s what they’re for – but it’s also bad, as it sets up expectation. In the same vein, it’s bloody irritating when you can feel an author searching around for something that they can’t quite grasp. It’s often obvious when a writer doesn’t quite know what’s happening. These are subtle things, obviously, but they’re both true. The trick is to keep the reader on their toes just enough ... too much and it’s unfocused, too little and it’s over-controlled. I’m not sure it’s a trick I’ve mastered.

So the answer to the “plot or pants” question is to plot with your pants on, and ride your plot by the seat of your pants. That’s what I try to do. Have enough structure to keep it coherent, and enough flexibility to keep it exciting. How much I succeed is another matter, of course. With apologies to Mike Tyson, everyone’s got a plan until their book punches them in the face.

Alex: Tell us about your latest novel.

Pete: My latest novel is called Killing Beauties: the chronicle of Susan Hyde, and it’s a work of historical fiction. Or fictionalised history. I’m not sure which. It follows a year in the life of Susan Hyde during the Interregnum of the 1650s, the period after the civil war(s) when Cromwell ruled the country. Susan, the sister of the king-in-exile Charles Stuart’s chief advisor Sir Edward Hyde, is sent on a mission to discover how John Thurloe, Cromwell’s Secretary of State and de facto spymaster, is uncovering all of the plots hatched by the royalist ‘secret’ society The Sealed Knot. Her job is to infiltrate his network, and then kill him. In this plot she is assisted by a firebrand called Diana Jennings and an all-female secret society called ‘les Filles d’Ophelie’, or the daughters of Ophelia. Things get out of hand ... and if I went any further, I’d be telling you the plot.

The book has two twists. The first is the plot twist, which I’m obviously keeping to myself, and the second is the fact that both Susan and Diana were real women who actually worked as spies for the royalist cause. Well, to be fair, Diana only ever truly worked for Diana Jennings, but that’s what made her such fun to write (and, hopefully, to read).

Alex: What was the first book you read?

Pete: I have absolutely no idea. I find it hard to believe that anybody does. Ant and Bee? Are You My Mother? Chariots of the Gods? I suppose it depends on what you think counts as reading. I was reading books about tank battles in World War II at home while at school we ‘read’ Enid Blyton.

Alex: How much research do you do and what does it usually entail?

Pete: It absolutely depends on the book. For BlackBeard’s Last Voyage (Santa and Pirates), I simply made the whole thing up. For my first (unpublished) novel, I naturally took my life as a research project, and wrote about the music business. My second was based on my grandfather’s memoirs about his escape from Burma when the Japanese invaded, and the stories he collected from other people involved, whether they made it out or were interned – so I read hundreds of letters that people sent to him. Actually, I’m seeing a pattern here ... oh my lord.

Apparently, I cheat. I trawl my own memory banks for useful material and if there’s nothing there I steal someone else’s work (obviously I make sure they don’t mind. I wrote to my grandfather’s correspondents to ask if I could use their stories, for example). I suppose this means I really like to go for known experience, whether mine or someone else’s (another example: I ran some pieces from another novel that revolved around something quite unpleasant past a mental health professional who looked at me with concern and asked me where I’d got them. My response that I’d just made them up worried her, but she eventually accepted that the imagination can be remarkably powerful). Sometimes there are strange connections. While writing a novel whose primary character suffered from dissociative identity disorder, I started dating a woman with DID. Not on purpose, I hasten to add. Messy, since you ask.

I wrote Killing Beauties because my partner (a historian) was researching women spies in the seventeenth century and, having extracted Susan and Diana from the archives, promptly told me I should write a book based on them. Their stories were quite fragmented (I mean, spies don’t tend to leave much evidence behind them. Not the good ones, anyway), but this was perfect for me. It gave me a certain path for them both, and an awful lot of blank spaces in between where they could get into trouble. I just took the history and filled in the blanks in the most interesting way I could. I used real letters, real events, and real people. I also invented letters, invented events, and invented people. And I did stuff in between. My PhD was on Francis Bacon (the other one), and I have lectured on early modern literature at various universities and do a lot of academic editing, mostly in seventeenth century historical studies. This means I have a good grounding in the period, and I know where to find specific things if I want to add ‘belt buckle’ realism. I have also read a lot of contemporary letters which gives a certain sense of how people thought, and of the rhythms of daily life and language. So yes, I cheated on this book, too. But research is like plotting. Too much and it infects your writing, drowning prose, plot and characters in a suffocating ... you get the picture. Too little and the book doesn’t work. Mostly I think I balance things pretty well, though there are, of course, some passages where I err too much on one side or the other. Getting the balance perfect is impossible, of course, because your reader’s knowledge and attitude also affect things. I’ve seen readers who complain of finding two historical errors in a book, adding that if they see a third, that’s it. Good luck finding an actual history book with only two or three errors, is all I can say to that! And then you have readers who are happy to have characters in a historical novel who are also vampires and live in two separate dimensions. That’s a fairly broad spectrum to balance, right?

Ultimately, I think you need enough research to make your work plausible (within its given parameters, of course), and to know that you have details that aren’t in the book at all. Fictional headroom, so to speak.

Alex: Do you ever base your characters on people you have encountered in real life?

Pete: Of course I do. We all do. Don’t we? When we create ourselves that’s exactly what we do. From the cradle to the grave. I also steal parts of characters in other books. Just like we do for ourselves, too. After all, what is real life, anyway? We’ve all read characters in books who are more strongly drawn than people we’ve met down the pub. That’s where the fun lies.

Alex: Which was the last book you read that blew you away?

Pete: Oh lordy, this is tough. A combination of Parkinson’s (I was diagnosed in 2008. That was fun), which has caused all sorts of problems with mid-level concentration as well as limiting the time that my brain will actually engage in a task, and the fact that I spend practically all my time writing, editing and researching means that I have probably written more books in the past few years than I’ve read for pleasure. The last two that really hit me were Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, which is as close to perfect as a book can be, I suspect, and one christmas day I read Primo Levy’s If This is a Man – if there is a more powerful indictment of man’s inhumanity to man, I don’t want to read it.

I do read to review on occasion, primarily for my stablemates from Unbound – Ewan Laurie’s Gibbous House (A favourite review of mine here - and its sequel No Good Deed are great fun, Tim Standish’s The Stirling Directive is a nicely dark piece of steampunk and Paul Waters’ Blackwatertown is more than worth a read.

Pete: I have absolutely no idea. I find it hard to believe that anybody does. Ant and Bee? Are You My Mother? Chariots of the Gods? I suppose it depends on what you think counts as reading. I was reading books about tank battles in World War II at home while at school we ‘read’ Enid Blyton.

Alex: How much research do you do and what does it usually entail?

Pete: It absolutely depends on the book. For BlackBeard’s Last Voyage (Santa and Pirates), I simply made the whole thing up. For my first (unpublished) novel, I naturally took my life as a research project, and wrote about the music business. My second was based on my grandfather’s memoirs about his escape from Burma when the Japanese invaded, and the stories he collected from other people involved, whether they made it out or were interned – so I read hundreds of letters that people sent to him. Actually, I’m seeing a pattern here ... oh my lord.

Apparently, I cheat. I trawl my own memory banks for useful material and if there’s nothing there I steal someone else’s work (obviously I make sure they don’t mind. I wrote to my grandfather’s correspondents to ask if I could use their stories, for example). I suppose this means I really like to go for known experience, whether mine or someone else’s (another example: I ran some pieces from another novel that revolved around something quite unpleasant past a mental health professional who looked at me with concern and asked me where I’d got them. My response that I’d just made them up worried her, but she eventually accepted that the imagination can be remarkably powerful). Sometimes there are strange connections. While writing a novel whose primary character suffered from dissociative identity disorder, I started dating a woman with DID. Not on purpose, I hasten to add. Messy, since you ask.

I wrote Killing Beauties because my partner (a historian) was researching women spies in the seventeenth century and, having extracted Susan and Diana from the archives, promptly told me I should write a book based on them. Their stories were quite fragmented (I mean, spies don’t tend to leave much evidence behind them. Not the good ones, anyway), but this was perfect for me. It gave me a certain path for them both, and an awful lot of blank spaces in between where they could get into trouble. I just took the history and filled in the blanks in the most interesting way I could. I used real letters, real events, and real people. I also invented letters, invented events, and invented people. And I did stuff in between. My PhD was on Francis Bacon (the other one), and I have lectured on early modern literature at various universities and do a lot of academic editing, mostly in seventeenth century historical studies. This means I have a good grounding in the period, and I know where to find specific things if I want to add ‘belt buckle’ realism. I have also read a lot of contemporary letters which gives a certain sense of how people thought, and of the rhythms of daily life and language. So yes, I cheated on this book, too. But research is like plotting. Too much and it infects your writing, drowning prose, plot and characters in a suffocating ... you get the picture. Too little and the book doesn’t work. Mostly I think I balance things pretty well, though there are, of course, some passages where I err too much on one side or the other. Getting the balance perfect is impossible, of course, because your reader’s knowledge and attitude also affect things. I’ve seen readers who complain of finding two historical errors in a book, adding that if they see a third, that’s it. Good luck finding an actual history book with only two or three errors, is all I can say to that! And then you have readers who are happy to have characters in a historical novel who are also vampires and live in two separate dimensions. That’s a fairly broad spectrum to balance, right?

Ultimately, I think you need enough research to make your work plausible (within its given parameters, of course), and to know that you have details that aren’t in the book at all. Fictional headroom, so to speak.

Alex: Do you ever base your characters on people you have encountered in real life?

Pete: Of course I do. We all do. Don’t we? When we create ourselves that’s exactly what we do. From the cradle to the grave. I also steal parts of characters in other books. Just like we do for ourselves, too. After all, what is real life, anyway? We’ve all read characters in books who are more strongly drawn than people we’ve met down the pub. That’s where the fun lies.

Alex: Which was the last book you read that blew you away?

Pete: Oh lordy, this is tough. A combination of Parkinson’s (I was diagnosed in 2008. That was fun), which has caused all sorts of problems with mid-level concentration as well as limiting the time that my brain will actually engage in a task, and the fact that I spend practically all my time writing, editing and researching means that I have probably written more books in the past few years than I’ve read for pleasure. The last two that really hit me were Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, which is as close to perfect as a book can be, I suspect, and one christmas day I read Primo Levy’s If This is a Man – if there is a more powerful indictment of man’s inhumanity to man, I don’t want to read it.

I do read to review on occasion, primarily for my stablemates from Unbound – Ewan Laurie’s Gibbous House (A favourite review of mine here - and its sequel No Good Deed are great fun, Tim Standish’s The Stirling Directive is a nicely dark piece of steampunk and Paul Waters’ Blackwatertown is more than worth a read.

Alex: How do you market your books?

Pete: This, I fear, is my greatest failing. I am in awe of people like Paul Waters who does such a great job of marketing himself (we share a publisher). I am simply incapable. I am almost pathologically averse to the telephone, and hate simply asking people to stock my book. I’ve never succeeded in getting a bookshop to stock me via email (and I have tried, lord I have tried). I do all I can. I’ve done blog tours, guest blogs, interviews (see www.killingbeauties.co.uk for links to these), but I can’t get off square one. You’d think a book about real women spies in the 1650s would be a gimme, right? Not in my hands. But it was the same when I was a musician – I was wildly praised by some very influential people, but never could translate it into anything meaningful. It truly is a mystery to me. Close but no cigar seems to be my motto. I almost got a film deal for Killing Beauties before it was published, so kept the broadcast rights. When it fell through, that was it. Trying to get an agent just for broadcast rights is impossible, it seems. And I don’t have a literary agent. No agent, no hope. I need a publicist, but cannot afford one, and so the circle closes on itself! It is wildly frustrating.

As for those who just think I don’t work at it hard enough, well, I think you misunderstand the problem.

Pete: This, I fear, is my greatest failing. I am in awe of people like Paul Waters who does such a great job of marketing himself (we share a publisher). I am simply incapable. I am almost pathologically averse to the telephone, and hate simply asking people to stock my book. I’ve never succeeded in getting a bookshop to stock me via email (and I have tried, lord I have tried). I do all I can. I’ve done blog tours, guest blogs, interviews (see www.killingbeauties.co.uk for links to these), but I can’t get off square one. You’d think a book about real women spies in the 1650s would be a gimme, right? Not in my hands. But it was the same when I was a musician – I was wildly praised by some very influential people, but never could translate it into anything meaningful. It truly is a mystery to me. Close but no cigar seems to be my motto. I almost got a film deal for Killing Beauties before it was published, so kept the broadcast rights. When it fell through, that was it. Trying to get an agent just for broadcast rights is impossible, it seems. And I don’t have a literary agent. No agent, no hope. I need a publicist, but cannot afford one, and so the circle closes on itself! It is wildly frustrating.

As for those who just think I don’t work at it hard enough, well, I think you misunderstand the problem.

Alex: What are your interests aside from writing? And what do you do to unwind?

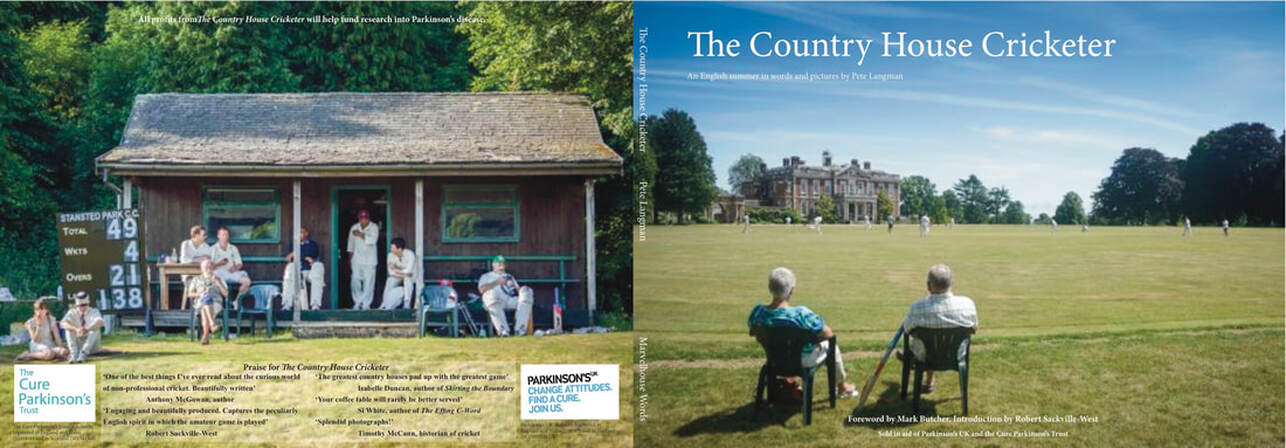

Pete: Cricket. I play cricket. Not particularly well (the Parkinson’s doesn’t help), but I love the game. I’ve published a fair few articles on the subject, too. That’s my escape. Sadly my lack of talent when combined with my physical challenges means I spend a lot of time scoring or taking photographs of my team mates. Luckily, that’s my other hobby. Photography. Mostly cricket and birds. I’m very partial to a diving pelican. There is no other creature that moves from clumsily, gawkily ugly to pure grace and back again in quite such style or with such speed. Astounding creatures. In 2015 I wrote a coffee-table book The Country House Cricketer in aid of Parkinson’s charities. I also still dabble in music, even though my guitaring abilities are now a mere shadow of their former glory. I’m currently involved in re-producing an old instrumental album of mine, adding guest musicians and with new drum and bass tracks, and remixing the lot – again, for the benefit of a Parkinson’s charity, Spotlight YOPD (young onset parkinson’s disease).

Alex: Which authors do you particularly admire and why?

Pete: I know so few that it’s hard to say. That may sound odd but I don’t find a connection between author and reader in the same way as I do musician and audience. Literature is at one remove from its creator, perhaps in a similar way to how we may feel Bach’s music without specifically feeling a connection to Bach, but will feel one with [insert favourite contemporary musician] when listening to their music. So I won’t say who I know that I most admire for fear of being accused of name-dropping (or failing to be able to drop names), but when it comes to oeuvre, it’s a different matter. I love Dickens, I suppose because he had such flaws (notable his inability to write realistic women of marriagable age) and yet still managed to write such brilliant books, both Banks (though latterly I felt Iain M. was rather more creative and interesting than Iain), stand in awe of Melville for a whole host of reasons, and Jim Crace, whose Quarantine is one of the most beautiful works I’ve ever cast my eyes upon. I could, like all writers, go on until I had persuaded myself never to commit another word to paper, ever. So best not.

My primary gift as a writer? I thought you’d never ask. Brevity.

Alex: Haha... and wow. It's been a real pleasure and absolutely fascinating listening to you, Pete. I'm going to have to grab a copy of Jim Crace's Quarantine. Interestingly, Paul Waters was the first author to appear on these pages, and I subsequently reviewed Blackwatertown on this website. Needless to say, I loved it. So on behalf of myself and this website's readers, thanks a million for coming on and sharing your incredible writing journey with us. It's been an education.

Pete: My pleasure, Alex.

Pete: Cricket. I play cricket. Not particularly well (the Parkinson’s doesn’t help), but I love the game. I’ve published a fair few articles on the subject, too. That’s my escape. Sadly my lack of talent when combined with my physical challenges means I spend a lot of time scoring or taking photographs of my team mates. Luckily, that’s my other hobby. Photography. Mostly cricket and birds. I’m very partial to a diving pelican. There is no other creature that moves from clumsily, gawkily ugly to pure grace and back again in quite such style or with such speed. Astounding creatures. In 2015 I wrote a coffee-table book The Country House Cricketer in aid of Parkinson’s charities. I also still dabble in music, even though my guitaring abilities are now a mere shadow of their former glory. I’m currently involved in re-producing an old instrumental album of mine, adding guest musicians and with new drum and bass tracks, and remixing the lot – again, for the benefit of a Parkinson’s charity, Spotlight YOPD (young onset parkinson’s disease).

Alex: Which authors do you particularly admire and why?

Pete: I know so few that it’s hard to say. That may sound odd but I don’t find a connection between author and reader in the same way as I do musician and audience. Literature is at one remove from its creator, perhaps in a similar way to how we may feel Bach’s music without specifically feeling a connection to Bach, but will feel one with [insert favourite contemporary musician] when listening to their music. So I won’t say who I know that I most admire for fear of being accused of name-dropping (or failing to be able to drop names), but when it comes to oeuvre, it’s a different matter. I love Dickens, I suppose because he had such flaws (notable his inability to write realistic women of marriagable age) and yet still managed to write such brilliant books, both Banks (though latterly I felt Iain M. was rather more creative and interesting than Iain), stand in awe of Melville for a whole host of reasons, and Jim Crace, whose Quarantine is one of the most beautiful works I’ve ever cast my eyes upon. I could, like all writers, go on until I had persuaded myself never to commit another word to paper, ever. So best not.

My primary gift as a writer? I thought you’d never ask. Brevity.

Alex: Haha... and wow. It's been a real pleasure and absolutely fascinating listening to you, Pete. I'm going to have to grab a copy of Jim Crace's Quarantine. Interestingly, Paul Waters was the first author to appear on these pages, and I subsequently reviewed Blackwatertown on this website. Needless to say, I loved it. So on behalf of myself and this website's readers, thanks a million for coming on and sharing your incredible writing journey with us. It's been an education.

Pete: My pleasure, Alex.