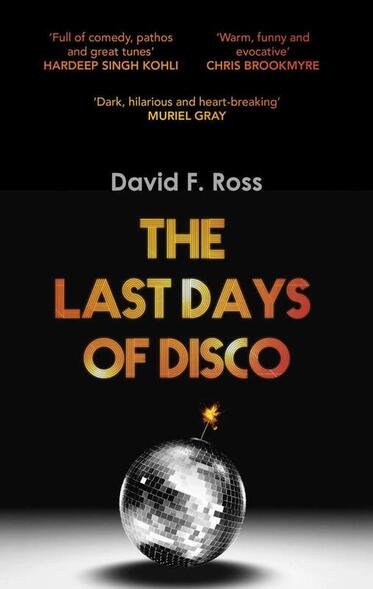

It gives me great pleasure to introduce readers to today's guest, David F. Ross, author of The Last Days of Disco, The Rise & Fall of the Miraculous Vespas, The Man Who Loved Islands, Welcome to The Heady Heights and There's Only One Danny Garvey

Alex: David, tell us a bit about yourself. Your background; where you were brought up; when you first began writing; your interests and so on.

David: I was born in Glasgow in 1964. I am an architect and writer. Since 2001, I have been a director of Keppie, the internationally successful design practice based in Glasgow.

My debut novel, The Last Days of Disco, was long-listed for the Best First Novel Award by the Author’s Club of London. National Theatre Scotland acquired dramatic rights for the book in 2015. I then completed a trilogy of Ayrshire-based books with The Rise & Fall of the Miraculous Vespas and The Man Who Loved Islands. All three novels have been translated into German, published by Random House. Welcome to The Heady Heights - my fourth for Orenda Books – was published in March 2019. I’m a regular contributor to Nutmeg and Razur Cuts magazines, and in December 2018 I was chosen to contribute a poem commemorating the 16th anniversary of the death of Joe Strummer for the publication Ashes to Activists.

I first began writing fiction around ten years ago. In the simplest terms, I had time to fill. I’d spent a lot of time working overseas in countries where there wasn’t much to do outside of the job, or where little English was spoken locally. Writing fiction – as opposed to articles about design - became a way of passing some of that time doing something creative that I increasingly enjoyed and found to be very therapeutic.

Alex: David, tell us a bit about yourself. Your background; where you were brought up; when you first began writing; your interests and so on.

David: I was born in Glasgow in 1964. I am an architect and writer. Since 2001, I have been a director of Keppie, the internationally successful design practice based in Glasgow.

My debut novel, The Last Days of Disco, was long-listed for the Best First Novel Award by the Author’s Club of London. National Theatre Scotland acquired dramatic rights for the book in 2015. I then completed a trilogy of Ayrshire-based books with The Rise & Fall of the Miraculous Vespas and The Man Who Loved Islands. All three novels have been translated into German, published by Random House. Welcome to The Heady Heights - my fourth for Orenda Books – was published in March 2019. I’m a regular contributor to Nutmeg and Razur Cuts magazines, and in December 2018 I was chosen to contribute a poem commemorating the 16th anniversary of the death of Joe Strummer for the publication Ashes to Activists.

I first began writing fiction around ten years ago. In the simplest terms, I had time to fill. I’d spent a lot of time working overseas in countries where there wasn’t much to do outside of the job, or where little English was spoken locally. Writing fiction – as opposed to articles about design - became a way of passing some of that time doing something creative that I increasingly enjoyed and found to be very therapeutic.

Alex: How would you describe your writing, and are there particular themes that you like to explore?

David: I think my writing is authentic, realistic and human. A sense of place is very important. I guess that might be to do with my natural interest in the architecture of a book, and in the universal truth that environment influences behaviour. I’ve always wanted my books to be immersive experiences, whether it’s in the identifications of attitudes that characters have for the times in which they live or simply the reinforcement of those times and how they shape actions; all of it is to cement the authenticity of the story for the reader, and to make them feel that my characters are believable and relatable. My books are characterised by the pursuit of often unattainable hopes and dreams, and the central characters are invariably from backgrounds that might be described as socially or economically challenging.

David: I think my writing is authentic, realistic and human. A sense of place is very important. I guess that might be to do with my natural interest in the architecture of a book, and in the universal truth that environment influences behaviour. I’ve always wanted my books to be immersive experiences, whether it’s in the identifications of attitudes that characters have for the times in which they live or simply the reinforcement of those times and how they shape actions; all of it is to cement the authenticity of the story for the reader, and to make them feel that my characters are believable and relatable. My books are characterised by the pursuit of often unattainable hopes and dreams, and the central characters are invariably from backgrounds that might be described as socially or economically challenging.

Alex: Are you a writer that plans a detailed synopsis or do you set out with a vague idea and let the story unfold as you write?

David: In general, I have written to a reasonably developed synopsis for the four books that precede my new book, There’s Only One Danny Garvey. This one had a different genesis, a different structure and a singular perspective. I guess I had the timeline of a football season in mind but Danny’s attitude to the people around him and to the limits of his environment emerged as the writing developed. The underlying theme of the book is personal isolation; of a gradual appreciation of the difference between loneliness and aloneness, and of trying to find redemption before it’s too late. I found writing the book without the safety net of a detailed story arc helped to heighten these often scary emotions, and I’m not convinced that would’ve been as affecting had it all been worked out in advance. It helped me to think like Danny; to understand more about his trauma and to react to new circumstances that prompt how he reacts. I certainly found the process intimidating and exhilarating in equal measure.

Alex: Tell us about your latest novel.

David: There’s Only One Danny Garvey is set 1996. It centres on a talented young footballer returning to his home village – and a host of dark and complicated family secrets – to manage his local Junior team after his playing career has ended abruptly.

Danny Garvey is a troubled individual. His narrative is increasingly unreliable. He isn’t unique in this; we all want people to see the best side of us, perhaps endeavouring to conceal what we are really like. I’m interested in the space between these two presentations of the self. Human frailty is more interesting as a subject to investigate, than untrammelled achievement. As Danny allows himself to care, to become even more vulnerable, he reveals more of his true self and the extent of the childhood trauma that has shaped him.

David: In general, I have written to a reasonably developed synopsis for the four books that precede my new book, There’s Only One Danny Garvey. This one had a different genesis, a different structure and a singular perspective. I guess I had the timeline of a football season in mind but Danny’s attitude to the people around him and to the limits of his environment emerged as the writing developed. The underlying theme of the book is personal isolation; of a gradual appreciation of the difference between loneliness and aloneness, and of trying to find redemption before it’s too late. I found writing the book without the safety net of a detailed story arc helped to heighten these often scary emotions, and I’m not convinced that would’ve been as affecting had it all been worked out in advance. It helped me to think like Danny; to understand more about his trauma and to react to new circumstances that prompt how he reacts. I certainly found the process intimidating and exhilarating in equal measure.

Alex: Tell us about your latest novel.

David: There’s Only One Danny Garvey is set 1996. It centres on a talented young footballer returning to his home village – and a host of dark and complicated family secrets – to manage his local Junior team after his playing career has ended abruptly.

Danny Garvey is a troubled individual. His narrative is increasingly unreliable. He isn’t unique in this; we all want people to see the best side of us, perhaps endeavouring to conceal what we are really like. I’m interested in the space between these two presentations of the self. Human frailty is more interesting as a subject to investigate, than untrammelled achievement. As Danny allows himself to care, to become even more vulnerable, he reveals more of his true self and the extent of the childhood trauma that has shaped him.

Alex: What was the first book you read?

David: The Blinder by Barry Hines. It’s less well known than A Kestral For A Knave and I’m perhaps the only person in the world who thinks it’s better. The book’s depiction of the red brick back courts of Northern England – and of the early 60s social context - is brilliant, and the characters are realistically flawed. I’m still slightly ashamed to admit that I stole this book from a small, local library as a kid. Although, since I still have the stolen copy, and it continues to inspired me now, then maybe they’d forgive me. Personally, I used libraries less than many other authors, I’d imagine. They weren’t places that I spent a lot of time in as a youngster (although arguably if I had, I’d have been in a lot less trouble) but I recognise the life-changing, and even life-saving, impact of access to library books for many. It’s devastating that many of them won’t survive the spending cuts that result from the current pandemic.

Alex: How much research do you do and what does it usually entail?

David: Not too much. I’m far too liable to be distracted by irrelevant detail, if I’m honest. And I’m not sure anyone - other than an examiner being paid to - really wants to read someone’s academic thesis; I know I wouldn’t. My books are written about people and their emotional interactions. That calls for observation and an intuition about the characters more than anything else. That said, for There’s Only One Danny Garvey, Alan Rough (the Scotland goalkeeper) was a helpful source of background detail from when he managed a successful Junior team in the early 90s, that I felt I owed it to him to add him in a brief cameo scene. I really hope he likes it.

Alex: Do you ever base your characters on people you have encountered in real life?

David: In common with many other authors, my first book is more autobiographical than the others. It draws more on my own experiences of being eighteen in 1982, and that of friends with whom I was close. I suppose it's inevitable that there's some of myself and my friends in the way the two teenage characters interact and speak, but beyond that, no. I've been extremely fortunate to have met many interesting people in my life and my characters are all generally amalgamations of characteristics and traits that I've found fascinating or remarkable. You become something of an observer as a writer; whether it’s in the mundane way people talk to each other, or their more extraordinary reactions to stress and pressure.

Alex: Which was the last book you read that blew you away?

David: The Sellout by Paul Beatty is just the best, most relevant, most scathingly funny and brutally realistic depiction of modern day America. The first hundred pages or so are perhaps the best fiction I’ve ever read, and reinforce a truism for me that writing critically acclaimed biting satire is the hardest literary skill to master.

Alex: How do you market your books?

David: With a new book coming out in January 2021; amid the tightest national lockdown restrictions yet, that’s a very good question. Social media profile is vital nowadays. A blog tour is organised over a month for all of the titles Orenda Books publish. Launch events are difficult to do on Zoom, and I think people are becoming a bit exhausted by them. My publisher organises promotion and media contact, and from that there are various radio and press interviews lined up. We will have a online launch event in February but I’m constantly looking for different and more creative ways to connect people to the previous material too.

For example, in lockdown I teamed up with a production company called Into Creative to produce an online VideoBook of my first novel The Last Days of Disco. It featured me – and several celebrity guests – reading the book in nightly episodes over a calendar month. It can be viewed using the link below:

https://intocreative.co.uk/the-last-days-of-disco-read-by-david-f-ross/

Without the opportunity to attend events, we also made a film in lockdown called ‘Miraculous’ with a script based on another of my books, The Rise & Fall of the Miraculous Vespas. This was funded, produced and filmed to promote Scottish Theatre at a time when its future was very uncertain. It can be viewed freely using the link below:

https://www.borderlinetheatre.co.uk/miraculous/

Alex: Which authors do you particularly admire and why?

David: Historically, George Orwell, Barry Hines and Colin MacInnes are significant influences. Of those still writing, Irvine Welsh, Andrew O’Hagan, Alan Warner and John Niven continue to be important reference points for me, especially in terms of authentic, socially realistic characterisation. Irvine Welsh – and Trainspotting especially - has changed the way the Scottish literary voice is appreciated around the world. Andrew O’Hagan and John Niven both come from an Ayrshire background and their books - specifically Niven’s The Amateurs - demonstrated that small-town everyday life could be emotionally affecting and brutally funny. Right now, there’s a new generation of Scottish writers whose work is phenomenal. Kirstin Innes’s Scabby Queen and Graeme Armstrong’s The Young Team are amongst the best I’ve read, with authentic, complex characters that I completely identify with from my own experience. And last but certainly not least, there’s David Keenan whose writing is truly unique, mesmerising and astounding … just like him.

Alex: It's been fascinating to talk with you David. Thank you so much for taking part and sharing this with readers.

David: No problem Alex. Thank you for the opportunity.

David: The Blinder by Barry Hines. It’s less well known than A Kestral For A Knave and I’m perhaps the only person in the world who thinks it’s better. The book’s depiction of the red brick back courts of Northern England – and of the early 60s social context - is brilliant, and the characters are realistically flawed. I’m still slightly ashamed to admit that I stole this book from a small, local library as a kid. Although, since I still have the stolen copy, and it continues to inspired me now, then maybe they’d forgive me. Personally, I used libraries less than many other authors, I’d imagine. They weren’t places that I spent a lot of time in as a youngster (although arguably if I had, I’d have been in a lot less trouble) but I recognise the life-changing, and even life-saving, impact of access to library books for many. It’s devastating that many of them won’t survive the spending cuts that result from the current pandemic.

Alex: How much research do you do and what does it usually entail?

David: Not too much. I’m far too liable to be distracted by irrelevant detail, if I’m honest. And I’m not sure anyone - other than an examiner being paid to - really wants to read someone’s academic thesis; I know I wouldn’t. My books are written about people and their emotional interactions. That calls for observation and an intuition about the characters more than anything else. That said, for There’s Only One Danny Garvey, Alan Rough (the Scotland goalkeeper) was a helpful source of background detail from when he managed a successful Junior team in the early 90s, that I felt I owed it to him to add him in a brief cameo scene. I really hope he likes it.

Alex: Do you ever base your characters on people you have encountered in real life?

David: In common with many other authors, my first book is more autobiographical than the others. It draws more on my own experiences of being eighteen in 1982, and that of friends with whom I was close. I suppose it's inevitable that there's some of myself and my friends in the way the two teenage characters interact and speak, but beyond that, no. I've been extremely fortunate to have met many interesting people in my life and my characters are all generally amalgamations of characteristics and traits that I've found fascinating or remarkable. You become something of an observer as a writer; whether it’s in the mundane way people talk to each other, or their more extraordinary reactions to stress and pressure.

Alex: Which was the last book you read that blew you away?

David: The Sellout by Paul Beatty is just the best, most relevant, most scathingly funny and brutally realistic depiction of modern day America. The first hundred pages or so are perhaps the best fiction I’ve ever read, and reinforce a truism for me that writing critically acclaimed biting satire is the hardest literary skill to master.

Alex: How do you market your books?

David: With a new book coming out in January 2021; amid the tightest national lockdown restrictions yet, that’s a very good question. Social media profile is vital nowadays. A blog tour is organised over a month for all of the titles Orenda Books publish. Launch events are difficult to do on Zoom, and I think people are becoming a bit exhausted by them. My publisher organises promotion and media contact, and from that there are various radio and press interviews lined up. We will have a online launch event in February but I’m constantly looking for different and more creative ways to connect people to the previous material too.

For example, in lockdown I teamed up with a production company called Into Creative to produce an online VideoBook of my first novel The Last Days of Disco. It featured me – and several celebrity guests – reading the book in nightly episodes over a calendar month. It can be viewed using the link below:

https://intocreative.co.uk/the-last-days-of-disco-read-by-david-f-ross/

Without the opportunity to attend events, we also made a film in lockdown called ‘Miraculous’ with a script based on another of my books, The Rise & Fall of the Miraculous Vespas. This was funded, produced and filmed to promote Scottish Theatre at a time when its future was very uncertain. It can be viewed freely using the link below:

https://www.borderlinetheatre.co.uk/miraculous/

Alex: Which authors do you particularly admire and why?

David: Historically, George Orwell, Barry Hines and Colin MacInnes are significant influences. Of those still writing, Irvine Welsh, Andrew O’Hagan, Alan Warner and John Niven continue to be important reference points for me, especially in terms of authentic, socially realistic characterisation. Irvine Welsh – and Trainspotting especially - has changed the way the Scottish literary voice is appreciated around the world. Andrew O’Hagan and John Niven both come from an Ayrshire background and their books - specifically Niven’s The Amateurs - demonstrated that small-town everyday life could be emotionally affecting and brutally funny. Right now, there’s a new generation of Scottish writers whose work is phenomenal. Kirstin Innes’s Scabby Queen and Graeme Armstrong’s The Young Team are amongst the best I’ve read, with authentic, complex characters that I completely identify with from my own experience. And last but certainly not least, there’s David Keenan whose writing is truly unique, mesmerising and astounding … just like him.

Alex: It's been fascinating to talk with you David. Thank you so much for taking part and sharing this with readers.

David: No problem Alex. Thank you for the opportunity.