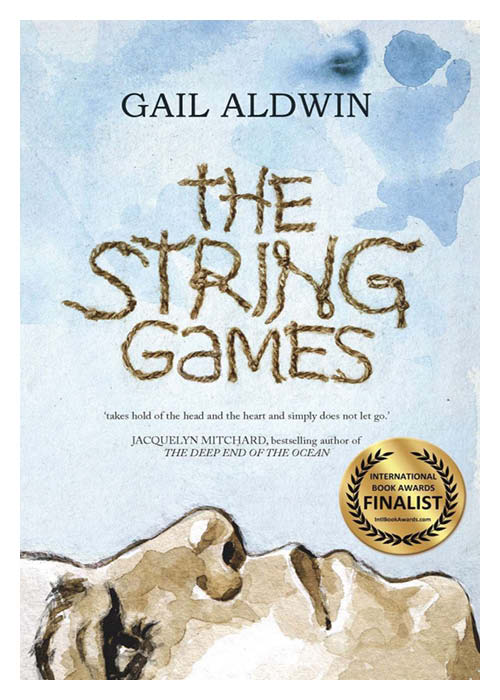

It gives me great pleasure to welcome Gail Aldwin onto the website today. Gail is a novelist, poet and scriptwriter. Her debut coming-of-age novel The String Games was a finalist in The People’s Book Prize and the Dorchester Literary Festival Writing Prize 2020.

Alex: Tell us a bit about yourself, Gail.

Gail: I’m Gail Aldwin, a Dorset writer currently living an itinerant existence thanks to redundancy from teaching. Before Covid-19, I volunteered at a refugee settlement in Uganda where I helped parents from South Sudan and the host community to support their young children’s learning. I’ve been writing for over a decade and am continually fascinated by the ideas that pop into my head.

Alex: How would you describe your writing, and are there particular themes that you like to explore?

Gail: My passion is for contemporary fiction. A novel is the biggest undertaking of all writing projects and perhaps the most rewarding. Pandemonium a children’s picture book I wrote with illustrator Fiona Zechmeister was great fun to create and involved in-depth collaboration – a whole different process from writing a novel independently. I continue to dabble in short forms of writing alongside drafting new works in progress. This exercises different creative muscles and as in cross training for a marathon, it helps to build the stamina needed to complete a long project.

Most of my novels include child characters and I explore themes such as intergenerational friendship.

Alex: Tell us a bit about yourself, Gail.

Gail: I’m Gail Aldwin, a Dorset writer currently living an itinerant existence thanks to redundancy from teaching. Before Covid-19, I volunteered at a refugee settlement in Uganda where I helped parents from South Sudan and the host community to support their young children’s learning. I’ve been writing for over a decade and am continually fascinated by the ideas that pop into my head.

Alex: How would you describe your writing, and are there particular themes that you like to explore?

Gail: My passion is for contemporary fiction. A novel is the biggest undertaking of all writing projects and perhaps the most rewarding. Pandemonium a children’s picture book I wrote with illustrator Fiona Zechmeister was great fun to create and involved in-depth collaboration – a whole different process from writing a novel independently. I continue to dabble in short forms of writing alongside drafting new works in progress. This exercises different creative muscles and as in cross training for a marathon, it helps to build the stamina needed to complete a long project.

Most of my novels include child characters and I explore themes such as intergenerational friendship.

Alex: What inspires you to write?

Gail: As humans, I think we all need a creative outlet. For others, it may be cooking or gardening or painting, but for me, it’s about writing. Ideas are like dandelion seeds floating in the air. I just have to reach out and grab one. I find the whole process of writing absorbing: from the terror of putting ideas onto a blank page to the gruelling process of getting a first draft down. Redrafting and editing is fun. I love the way stories become nuanced and layered with more detail and crafting applied. I find nailing the plot the biggest challenge and when it’s done, this brings the greatest satisfaction.

Alex: Are you a writer that plans a detailed synopsis or do you set out with a vague idea and let the story unfold as you write?

Gail: My debut coming-of-age novel The String Games was written as part of a PhD and this involved using the novel to experiment with different ideas, techniques and strategies linked to the research. As a result, the novel went through many, many drafts. Since then, I’ve plotted each novel to the nth degree to try and avoid going down fictional dead ends.

Gail: As humans, I think we all need a creative outlet. For others, it may be cooking or gardening or painting, but for me, it’s about writing. Ideas are like dandelion seeds floating in the air. I just have to reach out and grab one. I find the whole process of writing absorbing: from the terror of putting ideas onto a blank page to the gruelling process of getting a first draft down. Redrafting and editing is fun. I love the way stories become nuanced and layered with more detail and crafting applied. I find nailing the plot the biggest challenge and when it’s done, this brings the greatest satisfaction.

Alex: Are you a writer that plans a detailed synopsis or do you set out with a vague idea and let the story unfold as you write?

Gail: My debut coming-of-age novel The String Games was written as part of a PhD and this involved using the novel to experiment with different ideas, techniques and strategies linked to the research. As a result, the novel went through many, many drafts. Since then, I’ve plotted each novel to the nth degree to try and avoid going down fictional dead ends.

Alex: Tell us about your latest novel.

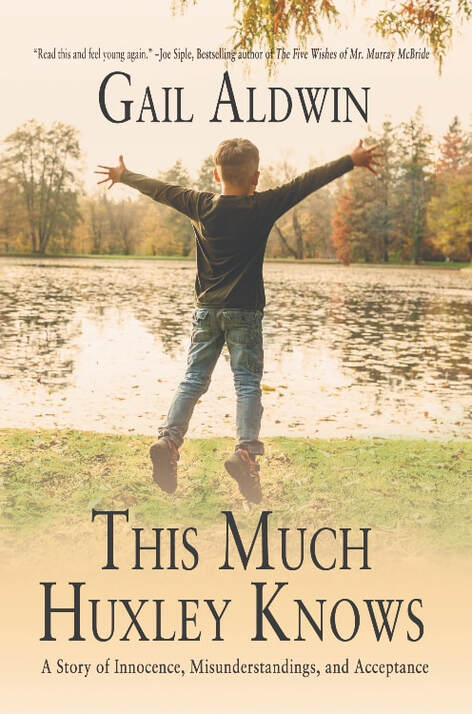

Gail: This Much Huxley Knows is contemporary fiction for adults and set in the school term following the Brexit referendum. It uses a young narrator to shine a light on community tensions. Huxley is seven years old and knows a lot about life but is particularly concerned with friendships. Ben is only his friend outside school, because he likes football and Huxley doesn’t. Samira is friendly, but she’s a girl. When Leonard, an elderly newcomer chats with Huxley at the barber’s shop, his parents are suspicious.

It’s been gratifying to received such a positive response to this quirky novel. Early readers have adored Huxley and found the concept unique.

Alex: What was the first book you read?

Gail: I was a non-reading child. By the age of eleven I could technically decode a text but I never saw books as a source of interest and pleasure. When I was seventeen and commuting into London for work, I started reading for enjoyment. The first novel I ever read was borrowed from my older sister. It was Jacqueline Susann’s Valley of the Dolls. I re-read it again recently and was pleased to see it’s considered a modern classic.

Alex: How much research do you do and what does it usually entail?

Gail: For every novel the research is different. In preparing to write This Much Huxley Knows, I read a lot of novels with child narrators to develop a unique voice for my young narrator. The character that influenced me most was six-year-old Billy in Chris Wakling’s What I Did. In the story, Billy misbehaves and is smacked by his father. This incident fuels the narrative when an onlooker reports the family to social care. Billy’s language is convincing and often hilarious. He uses idioms he’s heard but transcribes them incorrectly. We read a different cuttlefish instead of a different kettle of fish and drives him to destruction rather than drives him to distraction. Instead of using this same technique, I decided my character would purposefully wangle words to try and be funny. In this way, Huxley hopes to win friends.

I really enjoyed developing Huxley’s voice. At the beginning, I’d take any two or three syllable word and have a go at changing it into something a seven-year-old might find funny. Huxley has heard a lot about Brexit but calls it Breaks-it (there’s a sad truth in this corrupted word). At school, when Huxley’s asked to break down words into syllables, he, calls them silly-balls. He knows to wrap up warm to avoid pneumonia but changes the word to new-moan-ear. And so the jokes continue.

My current work-in-progress is a story about three couples holidaying on a tropical island when one of the wives goes missing. For this I watched an entire series of Married at first sight in Australia.

Alex: What is your writing weak point?

Gail: I’ve never been very good at spelling. Many words I simply learned to spell wrongly and don’t even realise I’ve made a mistake. When I was young and worked as a secretary, I used to carry a dictionary around in my handbag. Now, I’m forever looking up spellings online. Thank goodness I have a good proof reader for my novels or who knows what terrible spellings would slip through unnoticed by me!

Gail: This Much Huxley Knows is contemporary fiction for adults and set in the school term following the Brexit referendum. It uses a young narrator to shine a light on community tensions. Huxley is seven years old and knows a lot about life but is particularly concerned with friendships. Ben is only his friend outside school, because he likes football and Huxley doesn’t. Samira is friendly, but she’s a girl. When Leonard, an elderly newcomer chats with Huxley at the barber’s shop, his parents are suspicious.

It’s been gratifying to received such a positive response to this quirky novel. Early readers have adored Huxley and found the concept unique.

Alex: What was the first book you read?

Gail: I was a non-reading child. By the age of eleven I could technically decode a text but I never saw books as a source of interest and pleasure. When I was seventeen and commuting into London for work, I started reading for enjoyment. The first novel I ever read was borrowed from my older sister. It was Jacqueline Susann’s Valley of the Dolls. I re-read it again recently and was pleased to see it’s considered a modern classic.

Alex: How much research do you do and what does it usually entail?

Gail: For every novel the research is different. In preparing to write This Much Huxley Knows, I read a lot of novels with child narrators to develop a unique voice for my young narrator. The character that influenced me most was six-year-old Billy in Chris Wakling’s What I Did. In the story, Billy misbehaves and is smacked by his father. This incident fuels the narrative when an onlooker reports the family to social care. Billy’s language is convincing and often hilarious. He uses idioms he’s heard but transcribes them incorrectly. We read a different cuttlefish instead of a different kettle of fish and drives him to destruction rather than drives him to distraction. Instead of using this same technique, I decided my character would purposefully wangle words to try and be funny. In this way, Huxley hopes to win friends.

I really enjoyed developing Huxley’s voice. At the beginning, I’d take any two or three syllable word and have a go at changing it into something a seven-year-old might find funny. Huxley has heard a lot about Brexit but calls it Breaks-it (there’s a sad truth in this corrupted word). At school, when Huxley’s asked to break down words into syllables, he, calls them silly-balls. He knows to wrap up warm to avoid pneumonia but changes the word to new-moan-ear. And so the jokes continue.

My current work-in-progress is a story about three couples holidaying on a tropical island when one of the wives goes missing. For this I watched an entire series of Married at first sight in Australia.

Alex: What is your writing weak point?

Gail: I’ve never been very good at spelling. Many words I simply learned to spell wrongly and don’t even realise I’ve made a mistake. When I was young and worked as a secretary, I used to carry a dictionary around in my handbag. Now, I’m forever looking up spellings online. Thank goodness I have a good proof reader for my novels or who knows what terrible spellings would slip through unnoticed by me!